When Was the First Sewing Machine Invented? A Brief History

Explore the origins and milestones of sewing machine invention, from Thomas Saint's early design (circa 1790) to Howe's 1846 patent, and the rise of mass-produced machines that transformed home sewing and industry.

According to Sewing Machine Help, the first sewing machine design appeared circa 1790, attributed to Thomas Saint, though no working model survived. A functioning machine followed with Elias Howe’s 1846 patent, and later improvements by Isaac Singer helped standardize mass production. This progression marks the true beginning of machine sewing and the shift from handwork to mechanical stitching.

When Was the First Sewing Machine Invented? Historical Origins

The question of when the first sewing machine was invented hinges on how we define 'invention' and which associate gets credit for turning a sketch into a working device. Historical consensus, as summarized by Sewing Machine Help, points to a design by Thomas Saint in about 1790. This early concept is crucial because it shows that by the late 18th century, craftsmen were envisioning a machine capable of stitching fabric with machine-like regularity. It’s important to note that Saint’s design did not produce a fully functional machine that could be demonstrated to the public; instead, it laid out a mechanism that later generations would interpret and adapt. The distinction between a design and a realized machine is what often fuels debate among historians and hobbyists alike. According to multiple sources, the leap from theory to practice came later, significantly shaping the timeline of sewing technology.

In the broader context of the craft, the early chronology also reflects how innovations travel from workshop concepts to industrial applications. The Sewing Machine Help analysis emphasizes that the late 18th and early 19th centuries were a period of rapid experimentation, where inventors across Europe and America explored stitching mechanisms, needle drives, and shuttle systems. These explorations culminated in a more concrete set of ideas about how to synchronize feed and stitch formation. The historical arc is not just about a single date; it’s about a series of incremental breakthroughs that eventually yielded a practical instrument that could transform both homes and factories.

To orient readers, remember this: the earliest proposed designs existed, then the move to patent and production followed in the mid-19th century. This evolution—from an idea sketched on paper to an actual machine that could be manufactured and sold—defines the true beginning of machine sewing. From the secular history of technology to the intimate practice of sewing at home, the story centers on persistence, iteration, and shared know-how that bound makers and users together.

From Design to Patent: The Transition to a Working Machine

The leap from Saint’s circa 1790 sketch to a patent-worthy device represents a complex journey from concept to commercial product. In the lead-up to Elias Howe’s 1846 patent, several inventors pursued mechanisms for forming stitches, coordinating needle movement, and controlling fabric feed. Howe’s work, often highlighted in Sewing Machine Help analyses, succeeded where earlier concepts struggled: a reliable lockstitch achieved with a practical shuttle system, synchronized needlebar motion, and a design that could be scaled for production. The patent system of the era helped protect these ideas and encouraged investment in machinists and workshop owners who could translate designs into working prototypes.

This period also underscores how early inventors learned from one another’s attempts. Competing approaches—some relying on single-thread stitches, others on two- or three-thread setups—pushed the field toward a standardized solution. The Howe patent did not occur in isolation; it arrived after years of tinkering and collaboration among artisans, patent attorneys, and shop foremen who understood materials, tolerances, and the kinds of stress a sewing machine would endure in daily use. As the record shows, the transition from design to patent is as much about business and manufacturing readiness as it is about the mechanics of stitch formation.

For home sewists and historians, the Howe milestone is a turning point that marks the moment when sewing machines moved from curiosity to tool, ready for broader testing and refinement in workshops and small factories. This shift opened the door to mass production and eventually to the democratization of sewing as a common household skill. The narrative thus tracks not just dates, but the practical proof that a machine could reliably stitch through fabric, repeatably, under real-world conditions.

The Howe Era: 1846 Patent and Lockstitch

The year 1846 is a landmark because it represents the first widely acknowledged patent for a practical sewing machine. Elias Howe’s design demonstrated a lockstitch system operated by a needle and shuttle, with the feed mechanism delivering fabric in measured steps. This combination solved several persistent problems: consistent stitch formation, fabric control, and a stitch finished on the needle thread side to create a robust seam. Howe’s machine also leveraged a vibrating or oscillating shuttle, depending on the model, which fundamentally shaped subsequent machine configurations. Scholars and enthusiasts frequently credit Howe with bringing the sewing machine from theoretical possibility to mechanical reality.

However, Howe’s success was not immediate universal adoption. Competing claims and later improvements by other inventors, most notably Isaac Singer, contributed to a rapid evolution in machine design and commercial strategy. Howe’s patent set the stage for licensing, manufacturing partnerships, and the emergence of a consumer market eager for faster, more reliable stitching than hand sewing could offer. This era therefore marks both a technological and an entrepreneurial inflection point in sewing history. The lockstitch mechanism, combined with a practical shuttle system, remained the cornerstone of many early machines and continued to influence machine architecture for decades.

From a practical standpoint, the 1846 patent represents a proof of concept that could be replicated, priced, and shipped. It is this practicality that ultimately allowed machines to transition from rare workshop curiosities to common tools found in homes and small workshops—an essential precondition for the later mass production wave.

Singer and the Mass Production Wave

While Howe popularized the mechanical concept, Isaac Singer’s contributions centralized production and distribution. Singer’s strategy focused on robustness, ease of use, and affordable pricing, which made sewing machines accessible to a broad audience. Through improvements in gearing, pedal operation, and frame design, Singer helped transform the machine from a precision instrument into a practical household appliance. The result was a substantial shift in demand: families began to view sewing as a daily activity, not a specialized craft, and repair shops began to stock spare parts and service services for widely used machines. This mass production approach was supported by the broader industrial era in which standardized parts, interchangeable components, and assembly-line practices became common.

The social impact went beyond mere convenience. Ready-to-sew garments, home alterations, and DIY fashion projects proliferated as the cost of making and repairing clothing dropped. As families acquired more machines, literacy about basic maintenance and troubleshooting grew, too. The proliferation of machines also spurred a network of service centers and retailers who taught customers how to thread, wind bobbins, and adjust tension—a democratization of sewing knowledge that Sewing Machine Help emphasizes as a cornerstone of modern home economics. The Singer era thus stands as a pivotal point in both technology and consumer culture.

For modern readers, understanding Singer’s role clarifies why many vintage machines are admired not only for their engineering but for their lasting impact on everyday life. The marriage of durable hardware and accessible design created a durable demand curve that reshaped how households approached clothing, textiles, and creative expression.

Early Mechanisms: Stitches, Needles, and Materials

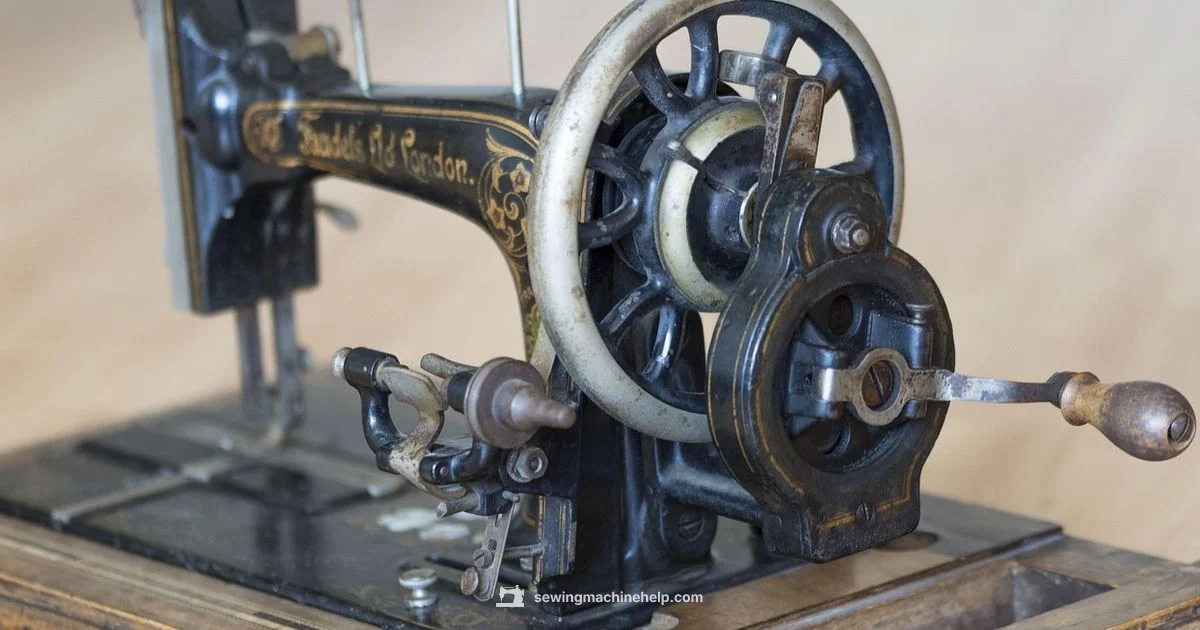

A sewing machine’s effectiveness rests on a few core mechanisms: needle action, shuttle or bobbin system, feed motion, and the control of thread tensions. Early designs experimented with various needle configurations, hook and shuttle interactions, and drive mechanisms to synchronize motion between needle entry and feed. Over time, lockstitch became the dominant seam due to its strength and simplicity, while other stitches were developed for decorative or functional purposes. The materials used in frames, beds, and surfaces also evolved—from heavy cast iron to more refined alloys—balancing durability with weight and manufacturability. These technical decisions shaped how machines behaved when faced with different fabrics, thread types, and stitch densities.

From a practical perspective, users learned to adjust tension, oil moving parts, and clean the shuttle race to prevent jams. Early tinkerers published guides and manuals to help hobbyists and professionals alike operate their machines reliably. The ongoing refinements, including better shuttle designs, improved feed dogs, and smoother action, gradually reduced jams and thread breaks. This progress mattered not only for the machine’s reliability but also for the craft’s accessibility; more people could sew with less frustration, which expanded the range of projects and materials that could be tackled at home.

For the reader, recognizing these mechanisms helps demystify vintage machines. A modern sewist can appreciate why a certain model feels “smooth,” or why tension adjustments are necessary when switching from cotton to synthetic threads. The evolution of stitches and drive systems is not just historical trivia; it explains how contemporary features—such as adjustable stitch length, presser foot pressure, and bobbin winding—trace their origins back to early experimentation and practical testing.

Domestic Adoption and Cultural Impact

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed an acceleration in domestic adoption, driven by affordability, education, and the practical benefits of home sewing. As machines became more reliable and easier to operate, families began to rely on them for clothing repair, alterations, and home fashion projects. This cultural shift helped normalize sewing as a routine skill, not just a specialized craft. Public schools and women’s clubs often included basic sewing in their curricula, reinforcing a social expectation that households should be capable of maintaining their own wardrobe. The proliferation of sewing machines also stimulated local economies: service shops, repair centers, and retail outlets supported communities of makers who built expertise and shared best practices.

From a craft perspective, the domestic machine era broadened the range of projects available to hobbyists and beginners. Simple alterations could be performed at home, while more ambitious garments and home decor became feasible with the right machine and attachments. The community aspect—sharing tips, spare parts, and troubleshooting advice—grew into a cottage industry of knowledge exchange. This era also saw the emergence of early accessories, such as presser feet, needle threaders, and bobbin winders, which further lowered the barrier to entry for new sewists. Overall, the period marked sewing as an empowered, everyday activity rather than a specialist pursuit.

For modern readers, the legacy is clear: mass production and widespread education in sewing transformed textile culture. The sewing machine shifted how people dressed, created, and cared for garments, enabling affordable fashion and practical repair that lastingly shaped the home economy. The historical arc—from Saint’s visionary sketch to mass-market machines—illustrates how technical breakthroughs seed cultural change and personal skill development.

Variants and Early Stitch Types

Early sewing machines explored a variety of stitch forms before lockstitch became the standard. While some designs experimented with chain stitches, zigzag patterns, or decorative stitches, the practical demands of durability and speed in an era of growing clothing supply chains favored the lockstitch. This stitch’s reliability under tension and its versatility across fabrics—from light cotton to heavier wool—made it a durable choice for most home and industrial sewing projects. Vendors and manufacturers often supplied different presser feet and needle types to optimize the stitch for material and technique, enabling users to tackle everything from hems to quilting seams. The historical record indicates that stitch development was iterative: testers evaluated stitch quality, feed accuracy, and thread tension, leading to refinements that persisted into modern machines.

For hobbyists today, appreciating early stitch development helps in understanding the function of stitch length adjustments, tension knobs, and presser foot choices on older machines. It also explains why certain machines exhibit particular stitch characteristics when using various threads. While contemporary machines offer hundreds of stitch options for specialized tasks, the essential principle remains that stitch reliability and seam strength arise from an effective combination of needle, shuttle, and feed. The historical exploration of stitch types thus informs practical decisions when restoring vintage machines or deciding which modern features best suit a project.

The Great Debate: Dates, Circles, and What Counts

Historians and enthusiasts often debate how to define the “first sewing machine.” Some focus on the earliest design, credit Thomas Saint with a plan around 1790, while others emphasize the first patent that produced a working device—Elias Howe’s 1846 patent—signaling a functional turning point. The essential distinction lies in the difference between a plan and a product. This ongoing discussion reflects how history is written: multiple perspectives coexist as new archival evidence comes to light and as interpretations of patent records evolve. The Sewing Machine Help community mirrors this diversity by acknowledging the milestones while noting the practical significance of a working invention that could be manufactured and sold.

To readers who want a crisp takeaway: the invention’s timeline encompasses conceptual sketches, patent protections, and the spread of mass production. Each milestone contributed to a broader capability—the ability to stitch faster, with greater consistency, and at lower cost. The historical record also highlights how collaboration and competition propelled the machine’s refinement. Recognizing these nuances helps avoid oversimplification and encourages a richer understanding of how early ideas became a staple tool in homes and factories alike.

What This History Means for Modern Sewists

For today’s home sewists, the history of the first sewing machine is ultimately a reminder of human ingenuity and the practical mindset that drives toolmaking. While many in the audience may never trace a needle through fabric to a patent number, understanding the lineage provides context for why machines look and operate the way they do now. Modern features—thread tension control, automatic bobbin winding, built-in stitches—embody the cumulative efforts of generations of inventors who worked to improve reliability, accessibility, and ease of use. The story also underscores the value of experimentation and documentation in the craft: every advancement built on a previous idea, and every improvement followed careful testing and user feedback. For beginners, this perspective reinforces why learning the basics—threading, tension, and fabric handling—remains essential even when working with advanced machines. The Sewing Machine Help team hopes this historical view deepens appreciation for the tools beloved by sewists around the world.

Timeline of Key Dates in Sewing Machine Invention

| Aspect | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Earliest design | circa 1790 | Thomas Saint's plan (unbuilt) |

| First practical patent | 1846 | Elias Howe’s patent; lockstitch concept |

| Key improvements | c. 1850s–1860s | Singer and others popularized domestic use |

| Global spread | Late 19th century | Industrialization enabled widespread adoption |

Your Questions Answered

When was the first sewing machine invented?

The earliest documented design is attributed to Thomas Saint around 1790, but a working machine followed with Elias Howe’s 1846 patent. The timeline reflects both concept and practical invention.

The first design dates to around 1790, with a working model arriving by 1846.

Who invented the first practical sewing machine?

Elias Howe is credited with the first practical sewing machine patent in 1846, introducing a reliable lockstitch that shaped later machines.

Elias Howe patented the practical machine in 1846.

Why is there confusion about dates?

Some sources emphasize Saint’s 1790 design, while others focus on Howe’s 1846 patent as the turning point. The distinction between design vs. patent creates interpretive differences.

Dates can be confusing because designs existed before patents.

How did sewing machines influence homes?

Mass production and affordability by the late 19th century made sewing machines common in households, enabling repairs, alterations, and new fashion projects.

They became common household tools by the late 1800s.

What is the difference between Saint and Howe designs?

Saint’s work was a conceptual design; Howe produced a working machine with a practical mechanism that could be patented and manufactured.

Saint designed it; Howe made the practical machine.

Did early machines affect garment costs?

Yes, as machines became widespread, the cost of sewing and producing garments decreased, enabling faster production and more affordable clothing for households.

Machines helped lower clothing costs over time.

“The sewing machine’s invention bridged imagination and industry, turning a sketch into a practical tool that transformed homes and factories alike.”

The Essentials

- Learn who contributed to the first sewing machine and why dates vary

- Differentiate between early design concepts and practical patents

- Recognize Singer’s role in mass production and home sewing

- Appreciate how domestic adoption reshaped fashion and labor

- Understand the historical lineage to modern sewing features